- by theguardian

- 21 Sep 2023

�Wallets and eyeballs�: how eBay turned the internet into a marketplace

�Wallets and eyeballs�: how eBay turned the internet into a marketplace

- by theguardian

- 18 Jun 2022

- in technology

One weekend in September 1995, a software engineer made a website. It wasn't his first. At 28, Pierre Omidyar had followed the standard accelerated trajectory of Silicon Valley: he had learned to code in seventh grade, and was on track to becoming a millionaire before the age of 30, after having his startup bought by Microsoft. Now he worked for a company that made software for handheld computers, which were widely expected to be the next big thing. But in his spare time, he liked to tinker with side projects on the internet. The idea for this particular project would be simple: a website where people could buy and sell.

Buying and selling was still a relatively new idea online. In May 1995, Bill Gates had circulated a memo at Microsoft announcing that the internet was the company's top priority. In July, a former investment banker named Jeff Bezos launched an online storefront called Amazon.com, which claimed to be "Earth's biggest bookstore". The following month, Netscape, creator of the most popular web browser, held its initial public offering (IPO). By the end of the first day of trading, the company was worth almost $3bn - despite being unprofitable. Wall Street was paying attention. The dot-com bubble was starting to inflate.

If the internet of 1995 inspired dreams of a lucrative future, the reality ran far behind. The internet may have been attracting millions of newcomers - there were nearly 45 million users in 1995, up 76% from the year before - but it wasn't particularly user-friendly. Finding content was tricky: you could wander from one site to another by following the tissue of hyperlinks that connected them, or page through the handmade directory produced by Yahoo!, the preferred web portal before the rise of the modern search engine. And there wasn't much content to find: only 23,500 websites existed in 1995, compared to more than 17m five years later. Most of the sites that did exist were hideous and barely usable.

But the smallness and slowness of the early web also lent it a certain charm. People were excited to be there, despite there being relatively little for them to do. They made homepages simply to say hello, to post pictures of their pets, to share their enthusiasm for Star Trek. They wanted to connect.

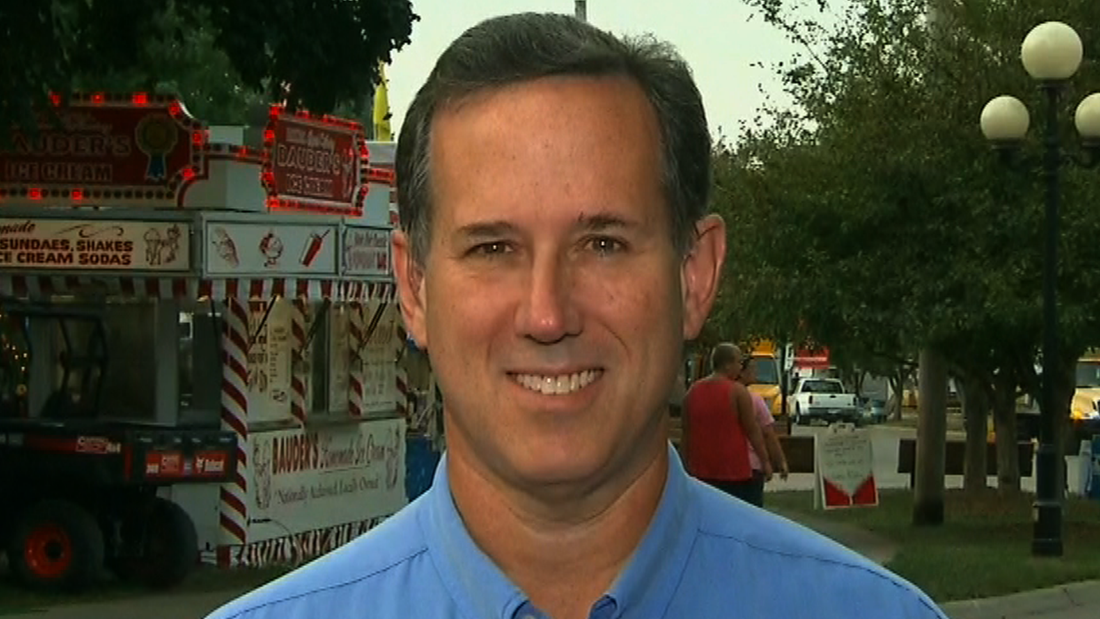

Omidyar was fond of this form of online life. He had been a devoted user of the internet since his undergraduate days, and a participant in its various communities. He now observed the rising flood of dot-com money with some concern. The corporations clambering on to the internet saw people as nothing more than "wallets and eyeballs", he later told a journalist. Their efforts at commercialisation weren't just crude and uncool, they also promoted a zombie-like passivity - look here, click here, enter your credit card number here - that threatened the participatory nature of the internet he knew.

"I wanted to do something different," Omidyar later recalled, "to give the individual the power to be a producer as well as a consumer." This was the motivation for the website he built in September 1995. He called it AuctionWeb. Anyone could put up something for sale, anyone could place a bid, and the item went to the highest bidder. It would be a perfect market, just like you might find in an economics textbook. Through the miracle of competition, supply and demand would meet to discover the true price of a commodity. One precondition of perfect markets is that everyone has access to the same information, and this is exactly what AuctionWeb promised. Everything was there for all to see.

The site grew quickly. By its second week, the items listed for sale included a Yamaha motorcycle, a Superman lunchbox and an autographed Michael Jackson poster. By February 1996, traffic had grown brisk enough that Omidyar's web hosting company increased his monthly fee, which led him to start taking a cut of the transactions to cover his expenses. Almost immediately, he was turning a profit. The side project had become a business.

- by travelpulse

- descember 09, 2016

Resort Casinos Likely Scuttled Under Amended Bermuda Legislation

Premier announces changes to long-delayed project

read more